Still Standing After All These Years

Part 13: Charlie Chaplin, “The Circus,” and Glendale Policeman Ralph Murdy, 1927

By Katherine Peters Yamada, March 2025

Photos from Glendale History Room unless otherwise noted.

Charlie Chaplin came to Glendale in 1927 to shoot the final scenes for “The Circus.”

Several crew members arrived early, about three a.m., with two of their most important props, according to an October 10, 1927 Glendale News-Press provided by film location expert Paul Ayers. Their early arrival was to allow Chaplin, who was directing, to secure “shots’ of the sun rising over the hills just east of Verdugo road.”

Chaplin was quoted as saying, “I have always been enthusiastic over Glendale. It is one of the beauty spots of Southern California. I want to personally thank the police department of the city for taking such good care of us.”

By this time, the movie was seriously behind schedule; it had been delayed by rampant development in Hollywood, and, according to charliechaplin.com, a scandalous divorce… “one of the most unseemly and sensational divorces of twenties Hollywood.’’ On top of that, a huge circus tent, the one where all the action was to take place, was destroyed by gale force winds and later, a fire destroyed more sets and props.

So, after all those calamities, Chaplin headed for Glendale, by then a popular film spot due to our proximity to Hollywood.

Chaplin Filmed on Site of Adventist Encampment

Chaplin chose a site that had previously been rented to the Seventh-day Adventists for an ‘encampment.’ The Adventists had established a presence here in 1905, purchasing the former Glendale Hotel for use as a sanitarium. By the 1920s, Glendale had become the center of medical services for the entire San Fernando Valley and the sanitarium had outgrown the old hotel. Administrators purchased another acre and expanded the facility to 100 beds, but even that was not adequate. In 1924, they purchased 30 acres on the outskirts of town and built a new complex. The Glendale Sanitarium Seventh-day Adventist Church opened that same year. It is now Vallejo Drive Church.

The Adventist encampment, their second in Glendale, was held on a triangular corner of Glendale Avenue and Verdugo Road, according to the Glendale Evening News, August 28, 1926. A huge tent provided seating for 8,000, while 800 smaller tents housed attendees. Elder J.A. Burden, who had opened the sanitarium in 1905, was a special guest. A cafeteria tent served up 2000 meals an hour, organized by Glendale resident I.E. Siebert and assisted by Mrs. A.C. Giddings, along with five chefs and a large staff. Paper umbrellas sheltered ladies from the intense August heat, while young boys scattered damp shavings around the grounds to control the dust. Ice cream cones, in a variety of flavors, were a popular treat. After ten days of events, the encampment closed.

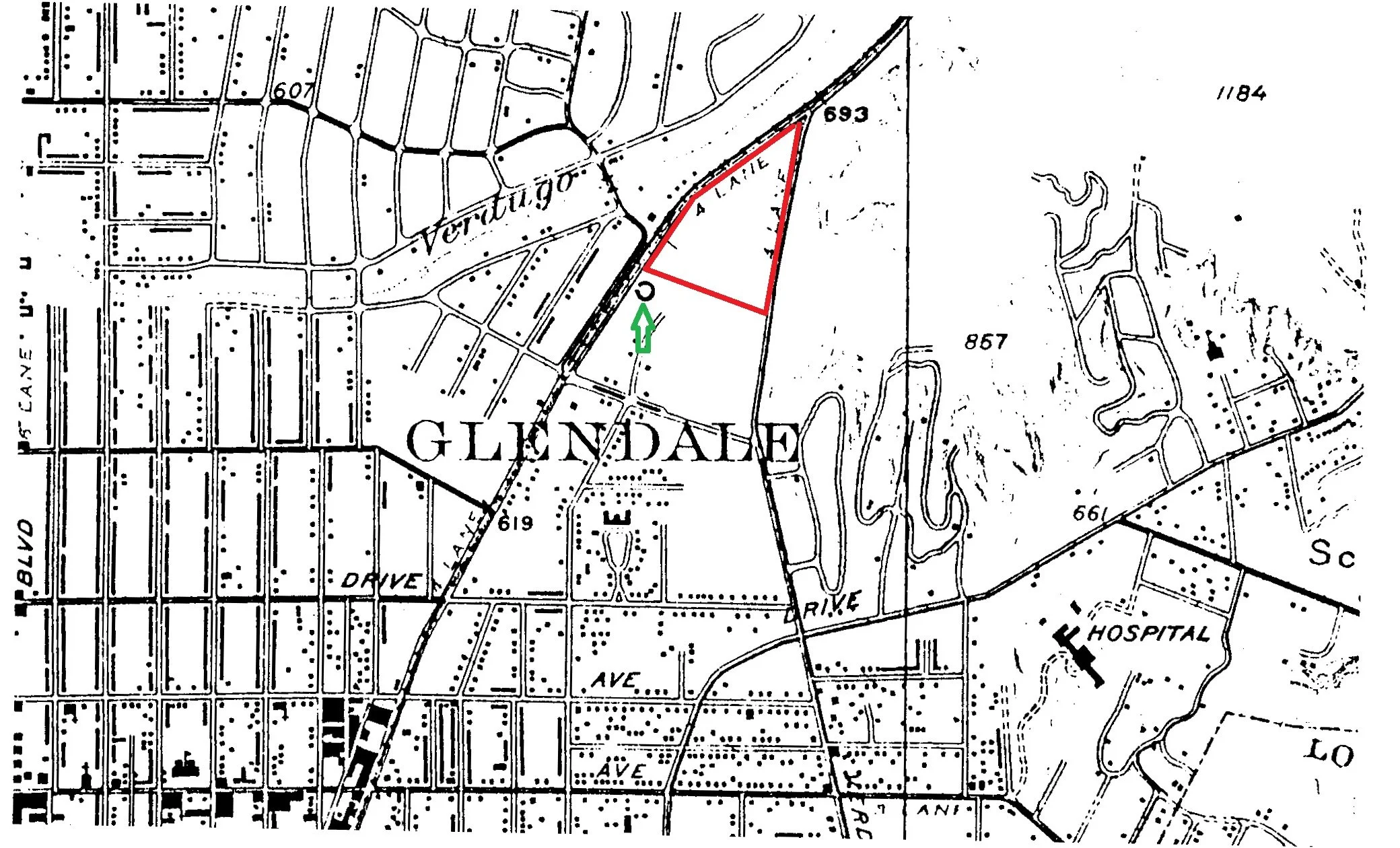

Ayers sent this copy of a Sanborn map, marking the location of the movie set with red, and a newspaper photo of the tent city with a green arrow pointing towards the Glendale Municipal Stables.

Sanborn Map, Courtesy, Paul Ayers

First Glendale Sanitarium

New Sanitarium on Wilson

1926 Tent City, Courtesy, Paul Ayers

Missing Props Delay Filming

The ‘important props,’ referred to above were two brightly painted circus wagons. One had the words ‘Pay Wagon’ on the side. As the fifty-person crew began arriving, the watchman, who had been out caring for the horses, discovered that both wagons were missing. The police were called. Assuming that bandits had mistaken the props for regular circus wagons, they began an all out search for the thieves.

Four hours later, they found the wagons in a rather unexpected place, on the UCLA campus, then on Vermont Avenue in Hollywood, (now the site of Los Angeles City College) as reported in the October 15, 1927 Los Angeles Times. They had not been taken by thieves looking for cash, but by students gathering fuel to build a bonfire before their annual football game with long time rivals, Occidental College. The bonfire took place without the extra fuel and the collegians “marched off to parade around Hollywood,’’ the Times story concluded.

Despite all the delays, filming finally began. And, by the way, it won an award for ‘Versatility and genius in writing, acting, directing and producing’ at the first Academy Awards in 1929.

Glendale Police Officer Ralph Murdy

During the filming, a policeman named Ralph Murdy, a champion boxer and former Marine, provided security. He was stationed there to keep traffic moving and to assist as needed.

Murdy had served during World War I. Later, he and his wife, Hazel, moved to Mexico, where he worked in the oil industry. There he contracted malaria.

Chaplin and Murdy, Courtesy, Sergeant Teal Metts, GPD

“The best treatment at the time was in Southern California,’’ according to Murdy’s granddaughter, Patricia Murdy Wolf. The couple moved here around 1923 so that Murdy could receive treatment and he later joined the Glendale Police Department. “I know he wasn't an officer very long because it was hard on my grandmother.’’

Coincidentally, Murdy wore a mustache similar “to the copyrighted Chaplin brush.’’ It caught Chaplin’s eye and he “insisted on a picture being made so that an official record can be kept of the similarity of the two soup strainers,” as noted in an unidentified clipping sent by Wolf. “In spite of the similarity of the decorative bristles on their upper lips, one of the men is a famous comedian, while the other is better known for his tear-making proclivities,’’ referring to Murdy’s sideline as a comedian.

Murdy offered to take the movie star for a ride on his police motorcycle, an event captured by a photographer and printed in the Los Angeles Examiner’s `Who’s Who in News of the Day,’ November 5, 1927.

Murdy and the Glendale Police Officers’ Relief Association

During the filming, Murdy told Chaplin he would be appearing in the Glendale Police Officers’ Relief Association show at the Alexander Theatre a few weeks later; so Chaplin taught him a few stunts. “Murdy contends that the mustache has greatly increased his salesmanship ability and that he has been able to dispose of a large number of tickets to the show since acquiring it,’’ according to the clipping.

Alexander Theatre Opened Two Years Earlier

Alex Theatre, 1925

It was the ‘ Roaring Twenties.’ Electricity, telephones and autos were affordable; and roads were going in. Women had gained the right to vote, flappers were wearing knee-length dresses and bobbing their hair, and motion pictures were all the rage.

Before 1922, few buildings were higher than two stories. Then, the three-story Pendroy Dry Goods went up on Brand, followed by the impressive six-story Security Trust and Savings Bank.

The movie theater opened on September 4, 1925 on North Brand Boulevard, in the heart of the growing town. It was one of the largest and earliest of the many extravagant movie houses then going up all over the area.

Glendale Police Officers' Relief Association

The Glendale Police Division established a five-man motorcycle squad in 1923 and began issuing an average of 450 tickets a month. The Glendale Police and Fire Association was formed that same year, according to a City of Glendale post online. The two entities separated the following year and the police organized their own Glendale Police Officers' Relief Association.

Funds raised at the Alexander and other similar events were to be used in case of sickness or accidents, and for death benefits. For instance, if an injury kept a policeman from his duties, he received three dollars a day for twelve weeks. Surgical reimbursements were not to exceed fifty dollars. If a member died while in good standing, his immediate family or dependent relatives received two hundred dollars.

Murdy Later Worked in Film Industry

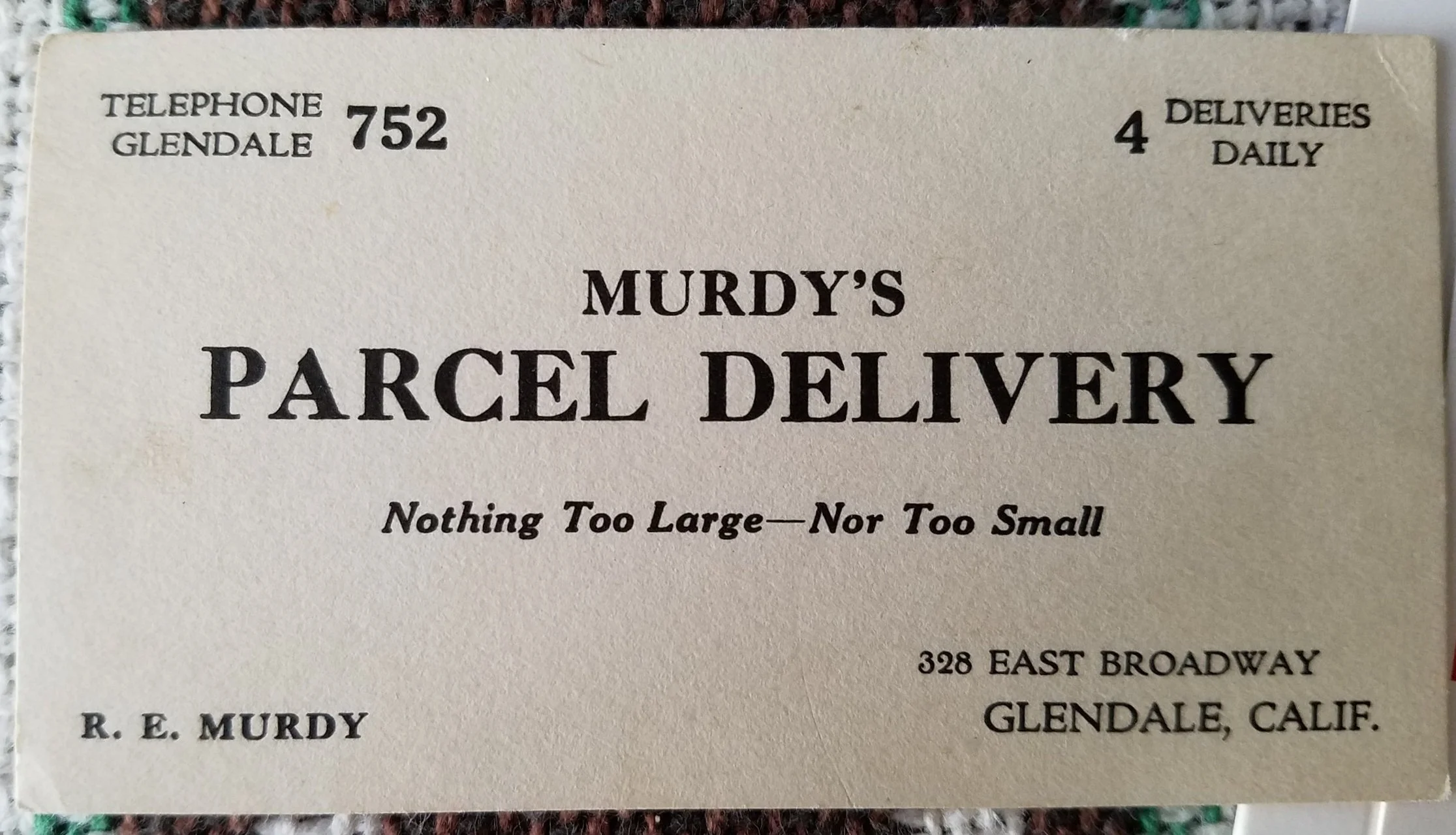

After he left the police force, Murdy opened a delivery service. Wolf sent a card for Murdy’s Parcel Delivery at 328 East Broadway: “Nothing Too Large - Nor Too Small,’’ Telephone Glendale 752, with “4 Deliveries Daily.’’ She also sent a photograph of son Wallace in the ‘delivery wagon.’

But the family left Glendale after losing their home - and the parcel delivery business - in the stock market crash, Wolf explained. “They moved all around Los Angeles looking for work and according to my Dad, lived in some pretty bad places.’’

During the Depression, Murdy worked as a film extra, Wolf added. Perhaps the publicity from his photo with Chaplin provided a link to Hollywood, as he appeared in a 1933 Laurel and Hardy production, “Sons of the Desert,’’ regarded as one of their best films, according to Wikipedia. In this photo, taken during filming, Murdy is seated in the center of the front row.

He was also in the original ‘’King Kong’’ as a journalist and worked in the new television industry in the 1940s. “He was a real character! He was a great singer, a comedian and a lover of people,’’ Wolf said of her grandfather.

‘Sons of The Desert’, Courtesy, Patricia Murdy Wolf

Business Card, Courtesy, Patricia Murdy Wolf

Son Wallace, Courtesy, Patricia Murdy Wolf

Murdy and Don Lee Television System, Courtesy, Patricia Murdy Wolf

Still Standing

Last Train Traveling South on Glendale at Broadway, Courtesy, Sergeant Paul Ayers.

The Glendale Police Museum, which opened in 2018 in the foyer of police headquarters on Isabel Street, is a treasure trove of nearly 120 years of local history.

Police historian and Sergeant Teal Metts acquired the Chaplin/Murdy photo from the Glendale Police Officers Association. They had received it from a Murdy relative, Sergeant Bill Wann, of the Sacramento Police Department.

Metts put me in email touch with Wann. “I didn’t know that Uncle Easton (his name was Ralph but he went by Easton) had been a police officer until my mom found that photo,’’ Wann replied. He learned from his mother, who grew up in Glendale, that Murdy was well liked and friendly, and had worked around movies. “The story goes that he took turns working security on movie sets and occasionally doing stunt work for the movies.’’

Curious as to where the photo had been taken, Metts contacted local film location expert Paul Ayers. Metts had discovered Ayers several years before, when he came across an online photo of one of the last trains to traverse the tracks on Glendale Avenue. (That was in 1956.) “As if that image wasn’t amazing enough, I also happened to see a police motorcycle in the background so I wanted to get a high resolution copy for us to archive.’’ When he discovered that the photo and the rights belonged to Ayers, he “connected with him and got the image.’’

Recalling Ayers’ skills as an historian, Metts sent him the Chaplin photo. “He was floored, and had never seen the photo before. He said he knew a Chaplin expert, John Bengtson, and would reach out to him.’’ The movie was identified: ‘The Circus’ (1928).

Police Officer Murdy, Courtesy, Sergeant Teal Metts, GPD

During the late 1920’s and early 30’s, there were only six or seven ‘motor officers’ in the local police department. Wondering if there were other Murdy photos, Metts dug into the archives and found a second photo, taken in 1928, of Murdy writing a traffic ticket in front of the old City Hall.

When Metts sent that photo to the Murdy family, he learned that they had never seen it. “These are the times in my role as a historian that are the most memorable… to reconnect stories, people, and in this case, a family with a photo.’’

Both Murdy photos are included in the police museum.

Glendale Citizens for Law and Order

Glendale Citizens for Law and Order was organized in 1967. Raymond D. Edwards served as first president of the group, formed to aid police and combat crime. They first distributed a pamphlet “You are the Eyes and Ears of the Law” and later printed one on marijuana. A film library was established for use in the schools.

Now known as the Glendale Police Officers Association, GPOA has about 250 members and continues to provides services such as “long term disability, legal defense funds, supplemental insurance and the Political Action Committee,’’ according to a City of Glendale online post. The GPOA formed the “Cops for Kids” foundation, to provide help to “children in under-privileged families during the holidays, and also provides scholarships to local students, and financially supports local events benefitting the youth of Glendale.’’

Glendale Police Foundation

Later, the Glendale Police Foundation came into being. It is a non-profit organization assisting the Glendale Police Department by providing essential resources and support necessary to foster community-police partnership and superior public safety, according to their website. Comprised of local Glendale community members, meetings are open to the public.

Police Museum Open to Public

Sergeant Teal Metts, curator, GPD Museum, Courtesy, KPYamada

The Glendale Police Department’s history, from its founding in 1906 to present day, is on display in the lobby of the headquarters on Isabel.

Four display cases include replicas of each major police uniform worn over the years. A model of a police helicopter hangs from the ceiling. The oldest and most valuable pieces, such as firearms, photos and badges, are kept in an enclosed area.

Bruce Hinckley, who was president of the foundation at the time, headed the fundraising campaign for the museum. It is open to the public during regular department hours: Monday through Friday, 8 a.m. to 5 p.m.

Resources

The Glendale History Room, on the second floor of the Central Library, has city directories dating back to 1906, photographs of early Glendale, and archival collections on the Glendale Unified School District, Forest Lawn, theaters of Glendale and other Glendale-related topics. Visits are by appointment only (please email glendalehistoryroom@glendaleca.gov)

Our local history was studied extensively by early historians, including John Calvin Sherer, who authored ‘History of Glendale and Vicinity’ in 1922. Carroll W. Parcher incorporated much of that information in `Glendale Community Book,’ published in 1957. A later version, ‘Glendale Area History,’ was published in 1974 and expanded in 1981. Unless otherwise noted, much of what is included here is from these books and from “Glendale, A Pictorial History.”

Other Resources

Verdugo Views, “Hotel Lives Again as Adventist Sanitarium”, August 24, 2002

Verdugo Views, “Glendale welcomed Alex Theatre in 1925”, August 27, 2015

Verdugo Views, “Officer Murdy Featured in New Police Museum”, August 24, 2019

Verdugo Views, “Finale of Chaplin’s movie filmed here in 1927” September 7, 2019

https://newsletter.alumni.ucla.edu/connect/2019/may/ucla-beginning/default.htm

https://www.charliechaplin.com/en/biography/articles/1-The-Circus

Glendale Police Foundation: https://gpf.org/about-the-foundation/