STILL STANDING AFTER ALL THESE YEARS

Part IX: Still Standing After All These Years: The Oak of Peace, the LA County Sheriff, Tiburcio Vasquez, and the Crescenta Valley, 1840s to 1870s

By Katherine Peters Yamada, Winter 2023

The area that is now Glendale is connected in several ways to events that began just before statehood.

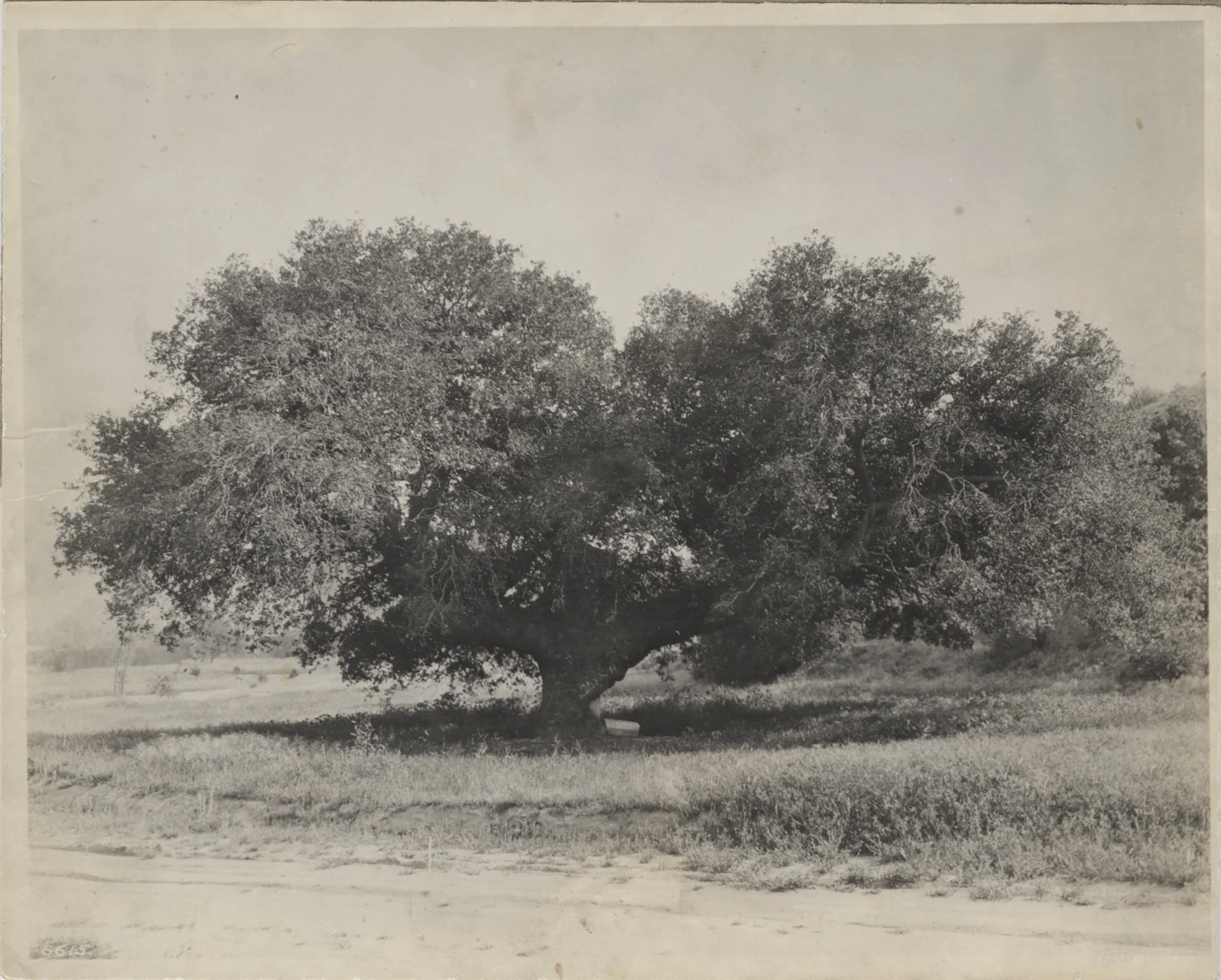

The story begins early in 1847, when two brothers met under an oak tree in what is now the Verdugo Woodlands. The two men, Andres Pico and Jesus Pico, were on opposite sides of the conflict between Mexico and the United States. General Andres Pico was the commander of the Mexican army and his brother, Jesus Pico, represented Lieutenant Colonel Fremont. The brothers discussed the surrender of Mexican forces due to the size and strength of Fremont's army, according to a City of Glendale website. The treaty was signed two days later by General Fremont and General Pico at Campo de Cahuenga.

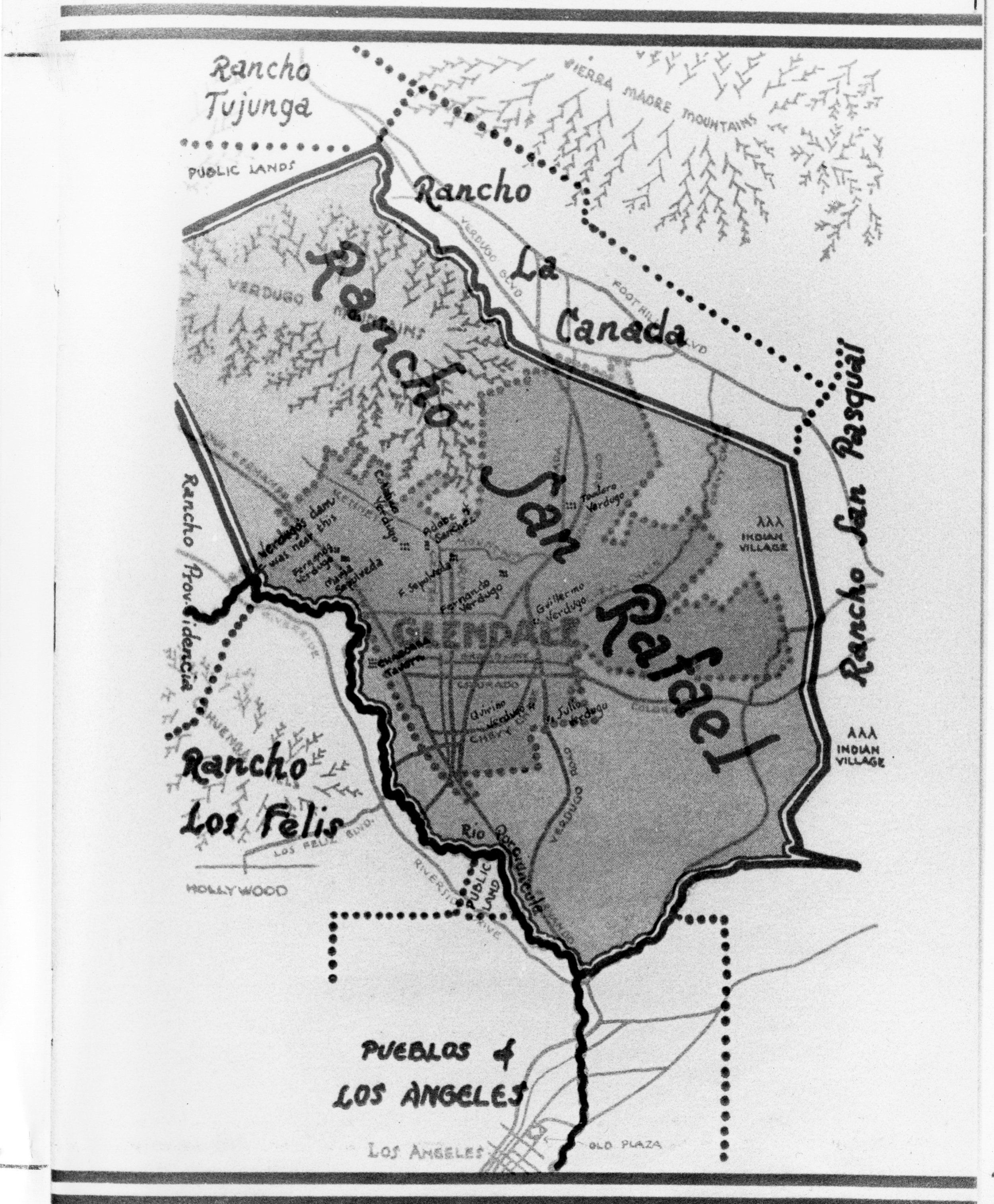

With the signing, the Mexican-American War came to an end and much of the Southwest was declared a territory of the United States. The tree where the brothers met stood on land given in 1784 to Jose Maria Verdugo, a soldier stationed at San Gabriel Mission. (A portion of his huge land grant later became Glendale.) The tree became known as the ”Oak of Peace.”

Oak of Peace. Credit: Glendale History Room

California Became a State in 1850

With statehood in 1850, came government and settlers. The Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, formed the same year, provided protection as settlers from eastern states and territories arrived in full force.

The new settlers took over Mexican-owned rancheros; land that had been in the same family for generations. Many felt slighted.

Verdugo Land Grant Intact for Less than 100 years

Like other Mexican landowners, the Verdugos rarely used cash; instead they bartered for goods. As Parcher’s 1981 book explained, “The Verdugos possessed land and its produce, but were perennially short on cash.”

Alas, the new arrivals wanted money, not livestock or produce.

Less than 100 years after Verdugo received the land grant, his son, Julio, took out a mortgage to build a house. When he defaulted, the matter ended up in court, leading to the 1871 dissolution of the estate. (For more on this, see Part II.)

Verdugo Land Grant Credit: Glendale History Room

Tiburcio Vasquez

This was the setting when the notorious bandit Tiburcio Vasquez arrived in the Southland. He would later claim that his criminal activities were “retribution for discrimination by the settlers and white norteamericanos (‘North Americans’) and that he was a defender of Mexican-American rights,” according to Wikipedia.

As Crescenta Valley historian Mike Lawler describes him, “Tiburcio Vasquez is one of the most colorful figures in California history. This bandit, both feared and admired, terrorized California from the 1850’s until his capture in 1874. He was a romantic figure - handsome and literate. He fashioned himself as a Robin Hood figure, robbing only the invading Americans, but not the Mexicans.

The Mexican population was sympathetic to the bandit, and unwilling to betray his movements to American sheriffs.”

Vásquez Born into Privilege

According to Wikipedia, Tiburcio Vásquez, born in Monterey in 1835, had an illustrious background. His great-grandfather came here with the De Anza Expedition of 1776 and his father, who served as a soldier of Spain, received land in exchange for his service.

Young Vasquez, a skilled marksman and excellent horseman, attended public school and spoke both English and Spanish, uncommon for the times. He was popular, especially with the ladies, and frequented Monterey balls and dances. Despite his upbringing, Vásquez was drawn in by Anastacio García, one of California's most dangerous bandits, in the early years after statehood.

In 1854, both Garcia and Vásquez were present at a dance when a Monterey constable was killed. Vásquez denied any part in the incident, yet he fled, becoming an outlaw.

Vasquez Heads for Southern California

After 20 years roaming northern and central California with Garcia, Vasquez formed his own gang. After a brutal robbery, he headed south.

Reports are that he hid out among the huge rock formations north of here. Eventually, he turned his attention towards what is now the Glendale area.

Lawler, a columnist for the CV Weekly, wrote: “He was very familiar with the canyons and trails of the San Gabriels above us, and regularly drove herds of stolen horses up to Chilao Flats near where Newcomb’s Café is today. There he would rebrand them and sell them north.”

Lawler explained that Vasquez’ movements are for the most part unknown today. “But one route to Chilao would have been Big Tujunga Canyon, and it’s fun to remember that the original name of Honolulu/Tujunga Canyon Road on the east side of CV was “Horse Thief Trail”.

One of the bandit’s most famous escapes was near the Crescenta Valley. The story starts in Montebello in April 1874, when Vasquez and his gang descended on the Repetto Ranch. Repetto had just sold a flock of sheep, and Vasquez was hoping to liberate the profit from the rancher. Unfortunately for Vasquez, Repetto’s cash was already in the bank in LA. Vasquez dispatched Repetto’s young nephew to withdraw the money, or his uncle would be killed. The terrified boy botched the withdrawal, the LA sheriff was alerted, and a posse set out for Repetto’s.

Vasquez spotted the dust from the galloping posse, and his gang took off towards the Arroyo Seco. Even with the law in pursuit, the bold bandit stopped near present day Devil’s Gate Dam to rob some Pasadena water company workers.”

Vasquez on Soledad Road, Now Angeles Crest Highway

From there, Lawler continued, Vasquez cut across La Canada to Soledad Road (now Angeles Crest Highway), which had been cut up the mountain just the year before.

“The winding wagon road climbed the San Gabriels as far as Dark Canyon, where it ended near the divide between the Arroyo Seco and Big Tujunga.

Darkness overtook both Vasquez and the posse just behind him. It was a moonless night and both the gang and the posse stopped until dawn. Vasquez said later that his camp was just 700 feet above the Sheriff’s posse, and he could have easily killed them all in the dark, but, confident he would escape, he let them live.

When dawn broke, Vasquez and his gang went over the divide and straight down the mountainside into Big Tujunga Canyon. Their escape route is today called Vasquez Creek, near Grizzly Flat, just to the east of Mt. Lukens.

Lawler wrote, “On the way down the nearly vertical slope, Vasquez’s horse tumbled and broke a leg. Vasquez pulled off his saddle and continued down the slope on foot. At the bottom, he dropped his saddle and one of his pistols, hitched a ride with one of his gang, and escaped out the canyon mouth near Tujunga.

From above, the posse watched the bandits ride down the vertical slope, and realized they couldn’t match their horsemanship. They turned around, and raced back down Soledad Road. At full gallop they followed the road west across La Canada, past where Verdugo Hills Hospital is today, and along Honolulu through the future Montrose.

Lawler added, “The posse galloped along Honolulu, up “Horse Thief Trail”, and over the pass to Tujunga. But Vasquez had already escaped into the desolate San Fernando Valley.

Two More Versions of This Chase

While researching Vasquez for a 2008 Verdugo Views column, this author read an account by Remi A. Nadeau, author of` ‘City-Makers.’ Nadeau was the great, great-grandson of Remi Nadeau who built a prosperous freighting business bringing silver from the Owens Valley mines to the wharf in San Pedro. There it was shipped to the mint in San Francisco.

Young Nadeau became interested in California history when he and his parents searched for remnants of the routes his ancestor had taken. As an adult, Nadeau began researching more local history. His 1948 book included a vivid description of Vasquez’ 1874 pursuit and their overnight halt. The next morning, Nadeau wrote, one of Vasquez’ men urged him to wait for the posse and ambush them but Vasquez refused, saying it would turn everyone, even his own friends, against them.

When I met then Glendale Police Chief Randy Adams at a 2008 community event, I asked him if there was any information on Vasquez in the department’s archives. He said he would send out a departmental email requesting information.

Star Barnum at Old Soledad Road, 1972 Credit: Mike Lawler

Captain Ray Edey replied, explaining that there are no references to Vasquez in GPD records, as the department wasn’t formed until Glendale was incorporated in 1906.

He added that Vasquez frequented the Chilao Flats of Angeles Crest. ‘’The only way he would be able to travel from Chilao to the San Fernando Valley and Los Angeles area would be by riding through Glendale. There are some local legends that place him hiding out in what is now Deukmejian Park in north Glendale.’’

Tiburcio Vasquez Credit: Mike Lawler

Vasquez Apprehended by Sheriff William Rowland

Soon after this chase, Sheriff William Rowland, who had been in office since 1871, came up with a plan to capture the notorious bandit.

Vasquez was hiding out near what is now the Sunset Strip in West Hollywood. The story is that Vasquez had seduced his own niece and that angry relatives turned him in. Rowland formed a posse, which went to the ranch, captured Vasquez and put him in the county jail. (For more, see Resources below.)

Later that month, Vasquez was taken, via steamship, to San Francisco. Following a four-day trial in San Jose, he was convicted and sentenced to death.

Amazingly, visitors, including many females, visited him in his cell. There he signed autographs and posed for photographs, bringing in funds to pay for his defense.

All to no avail; he was hanged on March 19, 1875 and buried in a Santa Clara cemetery.

Sheriff Mitchell Arrests Last Member of Vasquez Gang

Rowland’s four-year term as sheriff ended in 1875. He was succeeded by David A. Alexander, who served just one term, and then by Henry M. Mitchell.

Mitchell, who had been a member of the posse that captured Vasquez, served as sheriff only one year, but has gone down in history as capturing the last of the Vasquez gang in 1878.

The final chapter of Vasquez’ outlaw band took place in Verdugo Canyon, according to GPD Captain Mike Post, who authored “Pictorial History, Glendale Police Department 1851-1990.”

Post wrote: “The last member of the violent robber band was Miguel Sotello. Sheriff Mitchell discovered that Sotello was fond of a cantina in Verdugo Canyon, a wild area not yet envisioned as part of the La Crescenta residential area and miles from the existing small Glendale settlement.

Sheriff Mitchell and one of his deputies, Adolf Celis, set out, warrant in hand. As they rode up to the cantina, Sotello spotted their approach. Sotello leaped on his horse, and the chase began. For two miles of hard riding, the lawmen and the outlaw traded shots from horseback until finally Sotello fell from his mount, mortally wounded.”

The Vasquez gang was vanquished.

Still Standing After All These Years

There are many theories as to where Vasquez hid out while in this area: one is that he hid up in Dunsmore Canyon.

But Lawler has a different take. Here are excerpts from one of his columns in CV Weekly: “Dunsmore Canyon, now Deukmejian Wilderness Park, is mentioned in several histories of the bandit as one of his hideouts.

The original source of this connection comes from San Gabriel Mountains historian Will Thrall, who spent 50 years of his life researching Vasquez and writing on his findings.

Lawler referred to an article, "The Haunts and Hideouts of Tiburcio Vasquez," (Historical Society of Southern California Quarterly, June 1948) in which Thrall wrote: “The advance post and hideout from which he (Vasquez) raided the San Gabriel Valley and the whole Los Angeles area was in Dunsmore Canyon, north of Montrose on the south slope of Mt. Lukens. About a mile up from the mouth, where this canyon is split into two main branches, was an enormous oak tree so tipped toward the valley that its big top formed a perfect screen from below, almost completely blocking the canyon.

Thrall added, “In back of this natural screen, from which a man or horse could be seen approaching a mile or more away, Vasquez made his camp. From here, by passes to the east, south and west, he could easily watch the whole of Los Angeles County south of the mountains. Back of this camp a faint trail led up and over the ridge to the Dark Canyon/Vasquez Trail, with direct access to both the Arroyo and Big Tujunga and a network of trails spreading across the mountains in all directions.”

Lawler continued, “Will Thrall was a respected voice in the history of Vasquez, and so the story stuck that Vasquez had his main hideout here in La Crescenta. Newspapers eagerly reprinted the story, and local historians repeated it in their own history writings.

When the Le Mesnager family tried to sell Dunsmore Canyon to the state as parkland in the ‘60s, the Vasquez story provided some celebrity status to the property, and the CV Ledger newspaper printed several articles about the bandit’s hideout being in Dunsmore Canyon.

A well-meaning group from Glendale even had a bronze plaque placed in front of the Le Mesnager’s old stone barn which stated that “this” was Vasquez’s hideout. Although they may have meant the Canyon, many inferred that the barn, built in 1911, 37 years after Vasquez’s death, was the hideout.

When the City of Glendale acquired the property for the park it is today, they did extensive historical research on the Vasquez story and found nothing to support Will Thrall’s original story, and, of course, nothing to disprove it either. The city wisely put the misleading plaque in storage.”

The theory that Vasquez hid out in Dunsmore Canyon still gets repeated today. But Lawler has serious doubts about its validity. “The canyon doesn’t really split into two main branches, but just peters out in some nearly vertical box canyons. There is a trail out of the canyon, but it follows the ridgeline, and an escaping bandit wouldn’t leave himself exposed like that. The screening oak Thrall speaks of would perhaps be the McFall Oak? That’s the only big oak up there that could have hidden their camp, as Thrall wrote, but the view from there is not that great looking towards LA, and they could have been easily snuck up on.

Lawler concluded, “I hate to contradict old Will Thrall, but I tend to think he had his place names wrong. If Vasquez was in the Crescenta Valley at all, and I think he probably was, Pickens Canyon seems a more likely hideout, and it fits Thrall’s description better. We’ll never know for sure as the march of time puts us further from the truth.”

Pistol Found by Teenage Boy

The pistol dropped by Vasquez was found a few years later by a member of the Begue family.

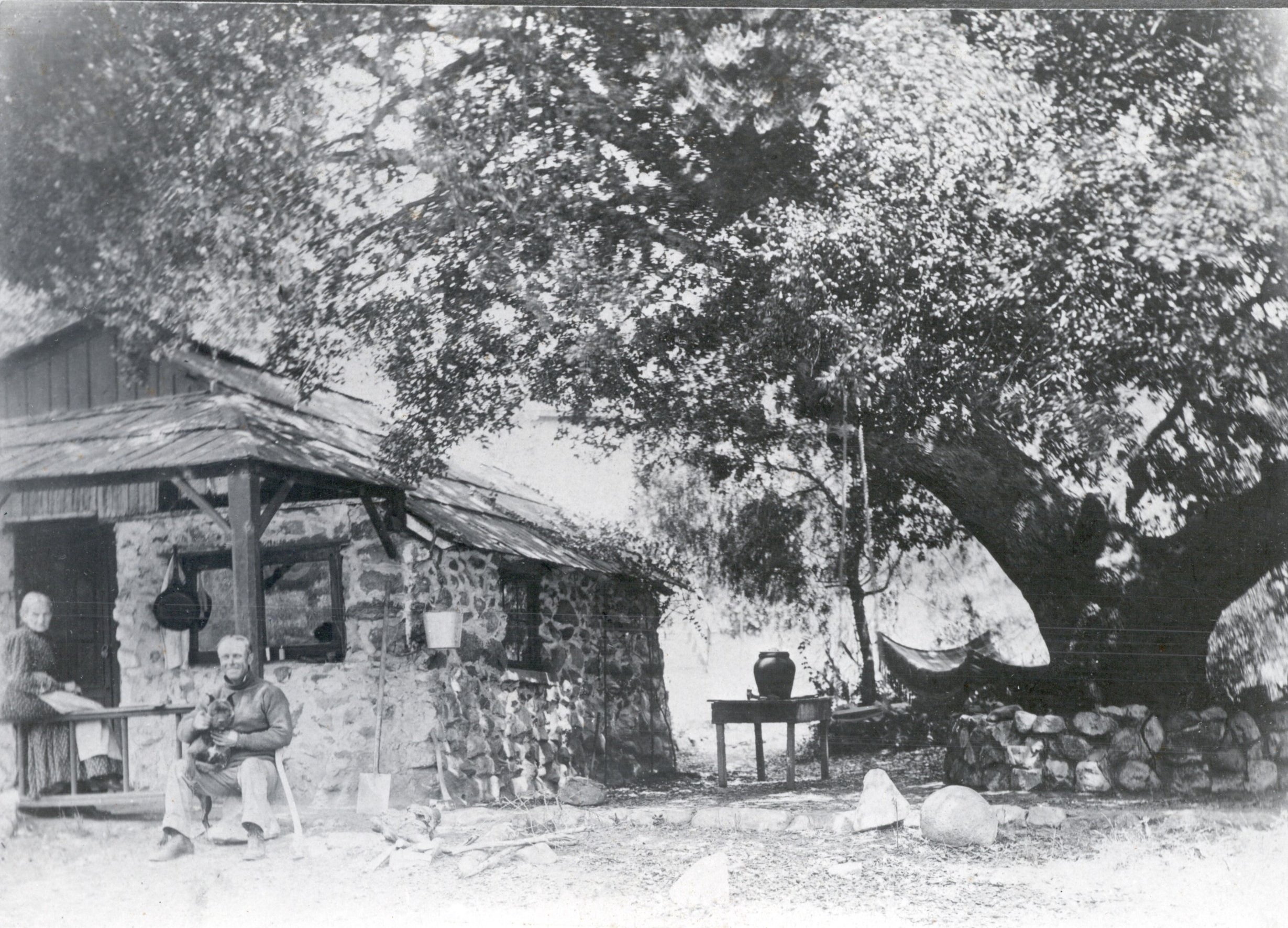

The Begues had moved to Las Barras Canyon in the early 1880s and built a stone house near a flowing spring. (The house stood on what is now the Verdugo Hills Golf Course.)

According to Lawler, the spring was the site of a seasonal Tongva village and later, in the 1700s, a stopping point for travelers between the San Gabriel and San Fernando missions.

The route became known as Horse-Thief Pass, as it was used by bandits driving their stolen horses from Los Angeles to the bandit’s corrals in the canyons of the San Gabriels.

The Begues built a barn, grew grapes and fruit trees, kept bees and operated a barbecue place on Foothill Boulevard.

According to John W. Robinson, writing in LA Westerner Corral newsletter in 1982, the pistol, with the initials “T. V.” carved on the barrel, was recovered by 16-year old Phil Begue in 1883. Years later his son sold it to Will Thrall, who in turn sold it to Westerner Ernie Kovak.

As an adult, Phil Begue served as a San Gabriel Timberland Reserve Ranger (later the National Forest Rangers).

The barn, which stood just south of Tujunga Canyon Road for more than 100 years, was demolished in 2004.

Dunsmore Canyon Land Now Deukmejian Wilderness Park

Much of Dunsmore Canyon, which may or may not have been where Vasquez hid out, is now the popular Deukmejian Wilderness Park.

The land, the largest remaining undeveloped parcel in Glendale at the time, was dedicated in December 1989 as a preserve.

Vasquez Rocks Natural Area Park

Another Vasquez hideout, now the 932-acre Vasquez Rocks Natural Area Park, is visible from the Antelope Valley Freeway (State Route 14) and is a popular filming location, according to Wikipedia.

Where are the Saddle and Pistol?

The whereabouts of Vasquez's gun and saddle are unknown. Various reports place them at the Natural History Museum, but that has not been verified.

Oak of Peace

The tree under which the two brothers met was some 300 years old at the time. It declined due to disease and was taken down several years ago.

In 2023, a new oak tree was planted by the Don José Verdugo Chapter, National Society Daughters of the American Revolution and the City of Glendale.

Side Note: Ninth County Sheriff Retired in Glendale

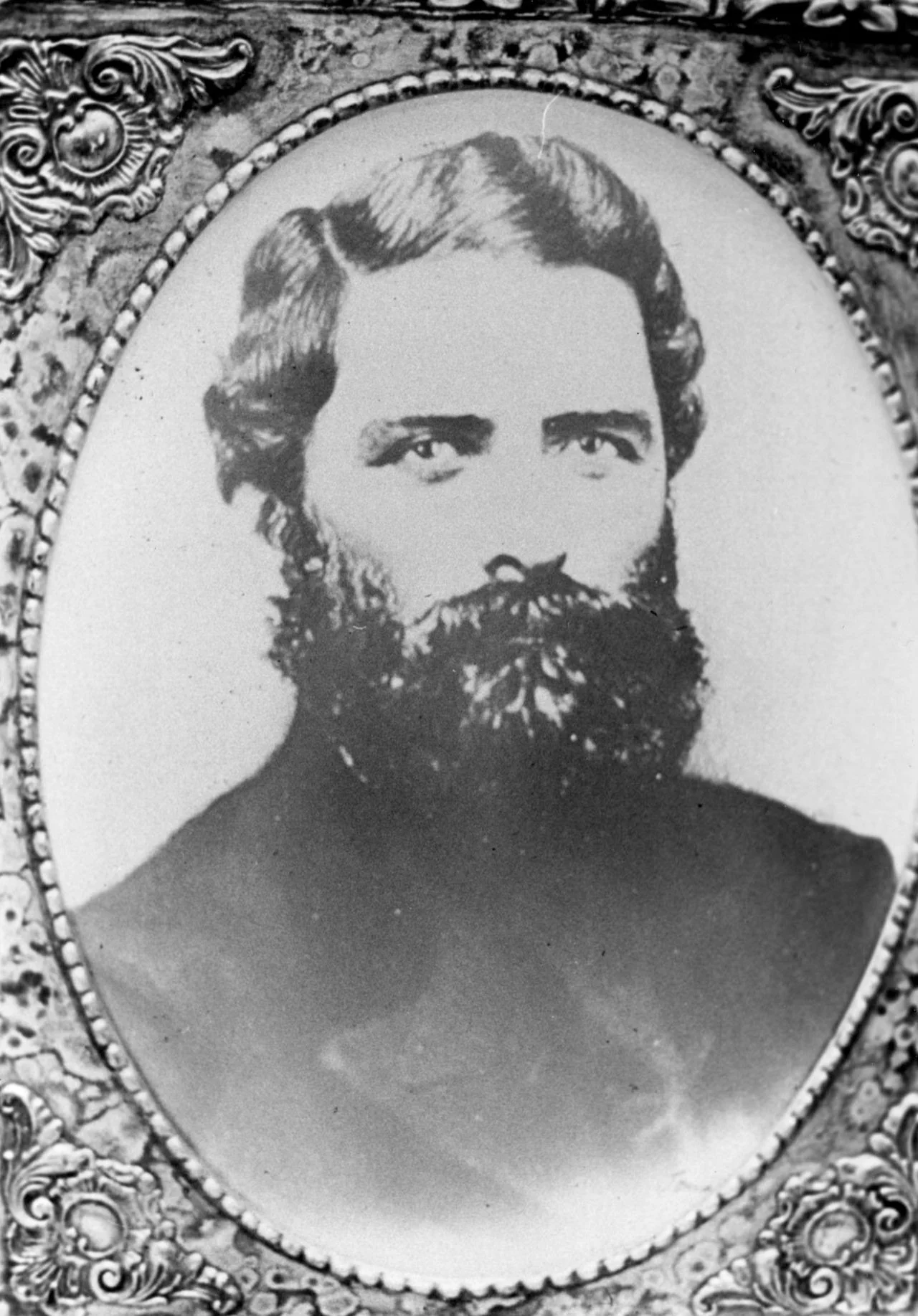

The ninth county sheriff, Tomas A. Sanchez, grandson of Vicente Sanchez, who had received a land grant that became known as Rancho Cienega, served as the county sheriff from 1859 to 1867.

Born in 1826, Sanchez was a Los Angeles tax collector in 1843 and fought with Mexican forces during the Mexican–American War.

He remained active under the new government and was elected sheriff in 1860. He was the first sheriff born in the county and served until 1867, well before Vasquez arrived. He married Maria Sepulveda, a member of the extended Verdugo family, during his last year in office.

He and his wife built a home in northwest Glendale and raised nineteen sons and two daughters. Sanchez died at age 56 in 1882.

Their house, the Casa Adobe de San Rafael, at 1330 Dorothy Drive, is a city landmark. (For more, see Part I.)

Begue Stone House Credit: Mike Lawler

Begue Barn. Credit Mike Lawler

Phil Begue. Credit: Mike Lawler

Tomas A. Sanchez. Credit: Glendale History Room

Maria Sepulveda. Credit: Glendale History Room

References

The Glendale History Room, on the second floor of the Central Library, has city directories dating back to 1906, photographs of early Glendale, and archival collections on the Glendale Unified School District, Forest Lawn, theaters of Glendale and other Glendale-related topics. Visits are by appointment only (please email glendalehistoryroom@glendaleca.gov)

Our local history was studied extensively by early historians, including John Calvin Sherer, who authored ‘History of Glendale and Vicinity’ in 1922. Carroll W. Parcher incorporated much of that information in `Glendale Community Book,’ published in 1957. A later version, ‘Glendale Area History,’ was published in 1974 and expanded in 1981. Unless otherwise noted, much of what is included here is from these books and from “Glendale, A Pictorial History.”

Other Resources

California State

Oak of Peace

Tibercio Vasquez

List of LA County Sheriffs

History of Ranchos

La Crescenta, Images of America, Mike Lawler and Robert Newcombe, Arcadia Publishing 2005

Pistol and saddle:

http://www.lawesterners.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/149-DECEMBER-1982.pdf

City-Makers: The Story of Southern California’s First Boom,’ Remi Nadeau, Trans-Anglo Books, Los Angeles 1965

Vasquez burial place, Santa Clara

“Pictorial History, Glendale Police Department 1851-1990,” author, GPD Captain MIke Post.

Vasquez Rocks

Deukmejian Wilderness Park

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1989-12-14-gl-230-story.html

Mike Lawler, Crescenta Valley historian and columnist, Crescenta Valley Weekly:

The Bandit Vasquez and Dunsmore Canyon: Just Another Legend? May 24, 2012

The Bandit Vasquez and the Crescenta Valley May 17, 2012

Verdugo Views, Glendale News-Press, Katherine Yamada, February 15, and 29, 2008